COP30 agrees on finance and forests but not on fossil fuel timelines

Author: PPD Team Date: November 23, 2025

The 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) concluded on November 22, having extended one day beyond its scheduled end. COP30 ended with the Global Mutirão Agreement, a political package that sets a new climate finance target and commits countries to prepare two major roadmaps. One will focus on ending deforestation, and one will outline a transition away from fossil fuels. The agreement avoided binding phase-out language, reflecting sharp divisions between developed and developing countries. The final Global Mutirão package, named after the Portuguese word for a collective effort, establishes a new annual climate finance target of $1.3 trillion (Rs 117 lakh crore) by 2035, a significant increase from the $300 billion base set at COP29.

India framed COP30 as the “COP of Implementation,” urging developed countries to move beyond pledges and demonstrate greater ambition through concrete action on technology transfer and financial commitments.

The Global Mutirão Package

The Global Mutirao package covers climate finance, adaptation, just transition and tools for tracking progress. Climate finance refers to funds provided by developed countries to developing countries under the Paris Agreement. The package commits to mobilising $1.3 trillion each year by 2035. It builds on the $300 billion annual target set in 2024. A two-year work programme under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement will examine how finance flows from developed to developing countries. The programme will look at finance gaps, transparency of financial flows and ways to design predictable funding systems.

Adaptation finance is set to triple by 2035 from 2025 levels. Current adaptation flows stand at $26 billion or Rs 2,340 crore each year. Developing countries’ needs are estimated at 310 to $365 billion by 2035. Adaptation finance supports climate-resilient infrastructure, early warning systems and disaster preparedness. COP30 also reaffirmed that under Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, developed countries have a binding obligation to provide climate finance. This recognition was a major win for developing countries.

The Belém Action Mechanism was set up as a cooperation platform for just transitions. COP30 also launched the Global Implementation Accelerator and the Belém Mission to 1.5 degrees Celsius to track national climate plan progress. Ten thematic agreements were adopted under the Global Mutirao. These cover technology transfer, loss and damage, the Global Goal on Adaptation, just energy transition and livelihood protection, and frameworks for implementation and transparency.

Fossil Fuels: Kept Out of Formal Text

Despite more than 80 countries, including Colombia, Germany, the UK, and the Alliance of Small Island States, calling for a fossil fuel transition roadmap. India, China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa opposed binding phase-out language. Their arguments focused on national energy needs, development priorities, inadequate finance and the rejection of uniform global timelines. India and other BRICS members (except Brazil) stated that energy transitions must be nationally determined. The outcome was a broad commitment to transition away from fossil fuels without timelines, mandatory pathways or binding requirements.

COP30 took place without an official United States delegation. This changed the dynamics and reduced the bargaining strength of developed countries. BRICS countries influenced the removal of fossil phase-out language, secured flexibility for developing nations and shifted focus to equity, economic justice and trade related climate barriers such as the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. This signalled a more multipolar climate governance landscape.

COP30 President André Corrêa do Lago announced Brazil would create two roadmaps outside the UNFCCC process: one on halting deforestation, another on transitioning away from fossil fuels. Colombia will host the First International Conference on the Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels in April 2026.

India, alongside Gulf States and Russia, supported keeping fossil fuel phase-out language out of the formal text. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva held a 20-minute closed-door meeting with Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav to discuss the fossil fuel roadmap, though no changes resulted from this engagement.

India’s Position and Outcomes

Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav led India’s delegation, delivering statements on behalf of BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, China) and the Like-Minded Developing Countries. India also coordinated positions through meetings with China’s Liu Zhenmin and held discussions with the UK’s Edward Miliband on technology transfer and climate finance.

India’s 2035 NDC was not submitted at COP30. Minister Yadav stated the submission requires “internal processes, including Cabinet approval” and announced India will submit its NDC by December 2025, along with its first Biennial Transparency Report (BTR). The original February 2025 deadline and subsequent September 2025 extension were both missed. India linked its submission to satisfactory progress on climate finance obligations.

India’s Climate Achievements Cited at COP30:

- 256 GW non-fossil capacity (including 190 GW renewables)

- 50%+ non-fossil power share (achieved five years ahead of schedule)

- 36% emission intensity reduction (2005-2020)

- 25.17% forest and tree cover

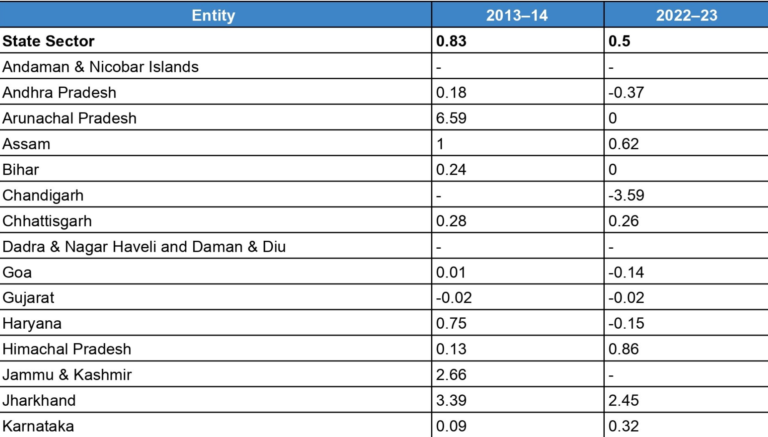

- 150%+ increase in adaptation expenditure (2016-17 to 2022-23)

- 2 billion plants planted in 16 months under community initiative

Brazil launched the Tropical Forests Forever Facility with $5.5 billion (Rs 49,500 crore) mobilised toward a $125 billion (Rs 11.25 lakh crore) target. Payouts to countries for ending deforestation begin in 2026. India joined the Tropical Forests Forever Facility as an observer, signalling its support for Brazil’s forest conservation initiative while opting not to take on member-level obligations.

India’s statement that “intellectual property and market barriers must not hinder technology transfer” advanced the Technology Implementation Programme. This is relevant to recent Indian energy sector developments in battery energy storage, green hydrogen, and grid infrastructure. India and Sweden launched an Industry Transition Platform with 18 industries and research institutions to use industrial by-products.

India pushed for COP30 to prioritise adaptation. Government data shows India experienced extreme weather events on 322 of 366 days in 2024 (88%), up from 318 days in 2023.

The tripling of adaptation finance by 2035 is relevant to Climate-resilient grid infrastructure, Transmission and distribution asset protection, and Weather forecasting for renewable energy integration.

India’s income loss from extreme heat was estimated at $159 billion (Rs 14.3 lakh crore) in 2021, representing 5.4% of GDP. This resulted from 167 billion lost labour hours across service, manufacturing, agriculture, and construction sectors, which is a 39% increase from 1990-1999 levels. Labour productivity is projected to decline by 5% at 1.5°C warming and 2.7 times more at 3°C warming.

Just Transition: Coal Workforce Framework

The Belém Action Mechanism establishes an institutional framework for just transitions. India’s coal sector employs approximately 4.5 lakh workers directly.

The mechanism provides for technical assistance and capacity-building but does not include dedicated finance from developed to developing countries.

India maintains 240 GW of thermal power capacity. The absence of fossil fuel phase-out mandates in the COP30 text preserves policy flexibility for managing this fleet.

Conclusion

UN Secretary-General António Guterres stated, “I cannot pretend that COP30 has delivered everything that is needed. The gap between where we are and what science demands remains dangerously wide.” COP30 culminated in a financial breakthrough but a planetary setback. The conference successfully established a new $1.3 trillion climate finance goal, tripled adaptation funds. While the Global Mutirão Agreement provides crucial tools and funding for implementation, its deliberate silence on the primary cause of climate change leaves a dangerous gap between diplomatic achievement and scientific necessity, ensuring that the conflict between energy sovereignty and global survival will dominate the agenda for years to come.

For India’s power sector, the outcomes provide a framework for accessing scaled climate finance and technology transfer while preserving policy flexibility on thermal capacity management. The Article 9 work programme will determine whether finance commitments translate into actual capital flows to Indian renewable projects over the next two years.

The featured photograph shows delegates from India, Sweden and the United Nations at a COP30 meeting, source: X/@byadavbjp.